Slopes of Curves, and the Curves themselves.

Let us make a little preliminary enquiry about the slopes of curves. For we have seen that differentiating a curve means finding an expression for its slope (or for its slopes at different points). Can we perform the reverse process of reconstructing the whole curve if the slope (or slopes) are prescribed for us?

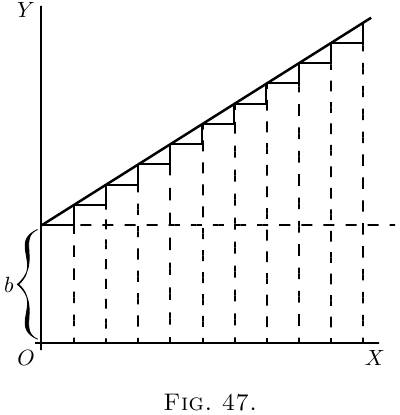

Go back to case (2) on here. Here we have the simplest of curves, a sloping line with the equation \[ y = ax+b. \]

We know that here $b$ represents the initial height

of $y$ when $x= 0$, and that $a$, which is the same as $\dfrac{dy}{dx}$,

is the “slope” of the line. The line has a constant

slope. All along it the elementary triangles

have the same proportion between height and base.

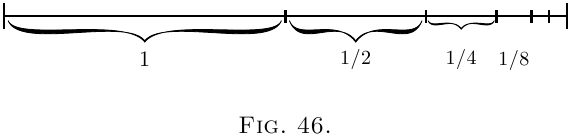

Suppose we were to take the $dx$'s, and $dy$'s of finite

magnitude, so that $10$ $dx$'s made up one inch, then

there would be ten little triangles like

Now, suppose that we were ordered to reconstruct

the “curve,” starting merely from the information

that $\dfrac{dy}{dx} = a$. What could we do? Still taking the

little $d$'s as of finite size, we could draw $10$ of them,

all with the same slope, and then put them together,

end to end, like this:

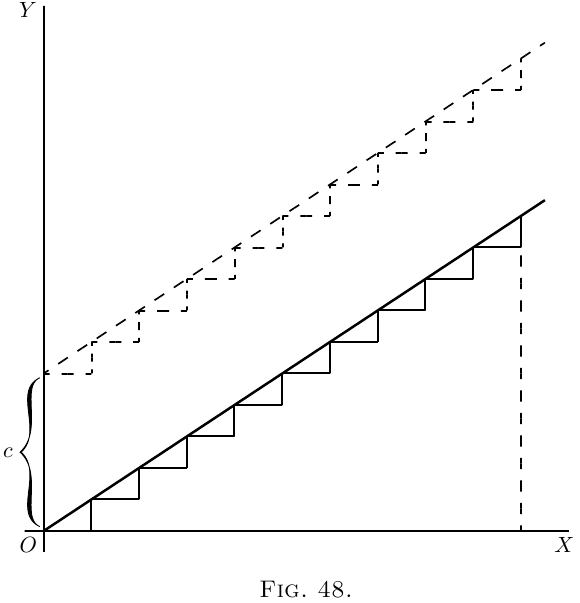

And, as the slope is the same for all, they would join

to make, as in Figure 48, a sloping line sloping with the

correct slope $\dfrac{dy}{dx} = a$. And whether we take the $dy$'s

and $dx$'s as finite or infinitely small, as they are all

alike, clearly $\dfrac{y}{x} = a$, if we reckon $y$ as the total of

all the $dy$'s, and $x$ as the total of all the $dx$'s. But

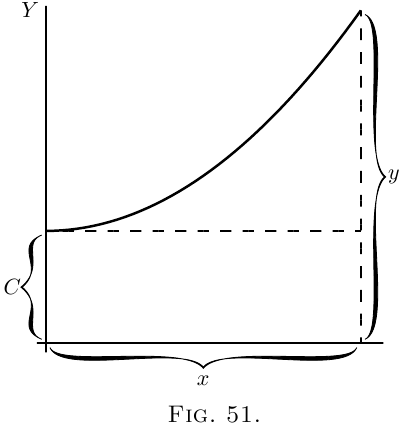

whereabouts are we to put this sloping line? Are

we to start at the origin $O$, or higher up? As the

only information we have is as to the slope, we are

without any instructions as to the particular height

above $O$; in fact the initial height is undetermined.

The slope will be the same, whatever the initial height.

Let us therefore make a shot at what may be wanted,

and start the sloping line at a height $C$ above $O$.

That is, we have the equation

\[

y = ax + C.

\]

It becomes evident now that in this case the added

constant means the particular value that $y$ has when

$x = 0$.

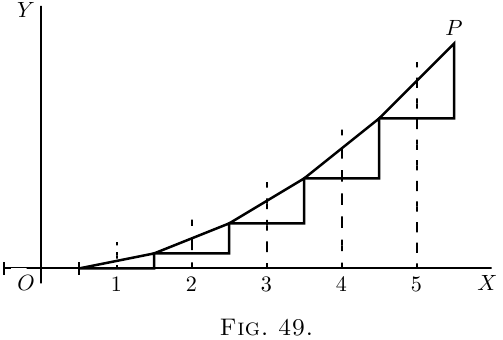

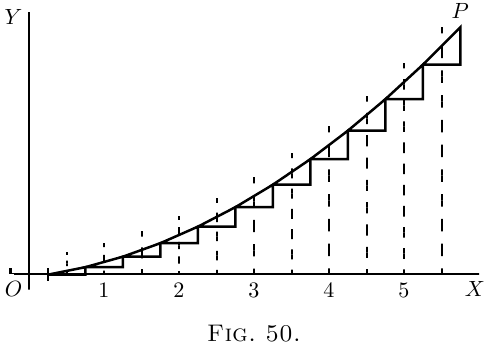

Now let us take a harder case, that of a line, the

slope of which is not constant, but turns up more and

more. Let us assume that the upward slope gets

greater and greater in proportion as $x$ grows. In

symbols this is:

\[

\frac{dy}{dx} = ax.

\]

Or, to give a concrete case, take $a = \frac{1}{5}$, so that

\[

\frac{dy}{dx} = \tfrac{1}{5} x.

\]

Then we had best begin by calculating a few of

the values of the slope at different values of $x$, and

also draw little diagrams of them.

When